Affirming Culture and Resisting Oppression: Selected Works of Chicana/o Art

The exhibition Images of Resilience: Chicana/o Art and its Mexican Roots has its foundation in the Chicano Art Movement known as “El Movimiento.” From the 1960s on, the Chicana/o Movement of both political and cultural development galvanized a generation of Mexican-American youth committed to civil rights. The Chicana/o Movement was at its deepest level a movement of social justice and cultural identity, where the right to land, language, education, and working wages was marked by an overriding theme of cultural reclamation. Many of these issues surrounding immigration, border politics, and cultural citizenship have arisen again today in a new era of immigrant concern.

Diego Rivera; Two Workers, 1938; Ink on paper, Collection of the Whatcom Museum, gift of the estate of William J. Eisner, 1975.110.39.

Within the context of the Chicana/o Movement for social justice, artists took their places in creating images and forms of art that would help enlist others in this movement for human rights. The work of individual artists and collectives was often anchored in community-based organizations such as the Galeria de la Raza, The Mexican Museum of San Francisco, Self-Help Graphics, the Social and Public Art Center, Plaza de la Raza in Los Angeles, and Centro Cultural de la Raza in San Diego. Across the country, the Guadalupe Center in San Antonio, the Mi Raza Center in Illinois, and later the Mexican Fine Arts Museum in Chicago, as well as El Centro de la Raza in Seattle, provided a base for individual artists and collectives. The seminal exhibition, Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation of the early 1990s, brought many of the artworks, centros, and collectives to a broader national awareness.

The early foundation of Chicana/o art has Mexican roots with the art of Los Tres Grandes—José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siquieros, and Diego Rivera. These Mexican artists reflect a time in the United States when their critical mural work was controversial, and later whitewashed. These Mexican artists were connected to the Mexicanidad Movement of the 1930s, and along with Frida Kahlo and others, were also a model for the Chicana/o Movement in the United States. The earliest works begun in the 1970s took public forms such as murals and posters as a means of educating and inspiring communities for social justice action in the US.

Images of Resilience features art from The Mexican Museum in San Francisco, The Steinbeck Center in Salinas, Calif., the Davidson Gallery in Seattle, and other collections, bringing the work of seminal artists to the Pacific Northwest for the first time in many years. While the Chicana/o art history presented here underscores issues and themes critical to the broader social movement, it is still relevant to the concerns of the largest ethnic group in the United States. The affirmation of community life represents what Tomás Ybarra-Frausto has called “nutrient sources,” which are the experiences of land, family, and spirituality. The artworks in this show embody many of these aspects from both rural and urban perspectives.

Public Forms of Expression

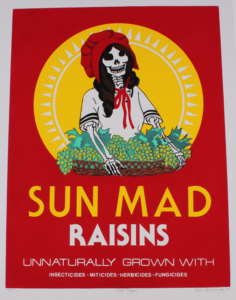

Works such as posters were central to the mobilization of social justice issues and the affirmation of community histories and cultural values. The work of Rupert García and Ester Hernández are some of the most prominent examples in this exhibition. García’s legendary prints and pastels helped to galvanize activists, and the image of the “Assassination of the Striking Mexican Worker,” based on Alvarez Bravo’s historic photo, was a profound inspiration in the movement. Hernández’s “Sun Mad” print, and later installation, honor the death of her father, and serve as an homage to farm-worker life. Hernández, like Carmen Lomas Garza and many others, contributed to the resurgence of the traditions of the Day of the Dead, which led to widespread celebration and contemporary art innovations in this country.

Rural and urban narratives

As the artists joined in with the larger activist community in both rural and urban settings, the work began to reflect both geographic and social imperatives. The Chicana narrative of Carmen Lomas Garza was manifested through the monitos, or flattened figure paintings, that recall with sinister familiarity a rural childhood. Healing, miracles, celebration, work, and death are all evoked with a loving, but bittersweet edge.

Urban expression was best embodied by the artists working in Los Angeles who had grown up in the shadow of Hollywood, and often near the freeways that bisected Chicana/o communities. The artists Carlos Almaraz, Gronk, Frank Romero, and John Valadez documented, interpreted, and transformed urban barrio (neighborhood) life. The artworks in Images of Resilience include paintings and pastels by Almaraz, and present expressionistic narratives of urban themes such as freeways and nightlife. Valadez’s hyper-realistic works have captured the characters of the urban terrain, while Romero’s historic “Crossing Whittier Boulevard” examines the powerful moments during the Chicano Moratorium March of Los Angeles in 1970. Gronk’s graphic work reflects the urban setting of Los Angeles’ café society, as well as his own alter ego in the painting, “Tormenta.” Within this same domain, the artwork of Enrique Chagoya challenges the socio-political realities through his use of ex-voto paintings created on tin and featuring pop icons and Catholic imagery.

In the Pacific Northwest, the textured and complex paintings of Alfredo Arreguín remain seminal iconography both within the Chicana/o world and in the larger art community. His rich depiction of Frida Kahlo has taken on an almost talismanic aura.

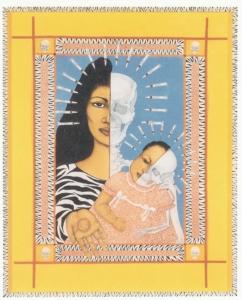

Cecilia Concepción Álvarez; Sí, Te Puede Pasar a Tí, El SIDA (altar detail)(Yes, It Can Happen to You, AIDS), 2002; Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist.

Women’s work

Despite struggles against patriarchy within the early movement, women artists developed images and work that brought new cultural and feminist meaning to the Chicana/o community, as well as insight into the lives of Mexican-American women. The often-contradictory aspects of race, class, and gender within a family placed Chicana activists in a unique position. This alternative chronicle is not simply about culture, but also about gender. Many of the works of Carmen Lomas Garza and Ester Hernández embody a gendered geography with images that both affirm and interrogate domestic life and depict imagery on women’s terms. The work of Seattle-based artist Cecilia Concepción Alvarez also presents gendered geography, but from a Pacific Northwest perspective.

Urban aspects of women’s work is represented in the art of Patssi Valdez, an early member of the art collective, Asco (from the Spanish word meaning nausea). Valdez’s artwork moves from Asco walking murals to photography to painting. Her spinning rooms and turbulent disturbances in the domestic site represent a subtle feminist critique of the idealized home. In her mixed-media and found object installations, Valdez uses discards and remnants of glamour and decay to imply an impending violence and danger in the urban sphere.

Images of Resilience provides insight into the wide range of iconic paintings, prints, and pastels that express the complexity of the Mexican-descended community, whose identity as Chicana/os is born out of a profound social struggle that still has meaning today. In an era of growing xenophobia and virulent anti-immigrant sentiments, it is important to present the cultural contributions and artistic legacies of one of the earliest, and now largest, ethnic communities in the United States.

By Amalia Mesa-Bains, Artist, Scholar, and MacArthur Fellow

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!